One day, you may be asked to play Cranium in a language/culture that is not your own. You should heed this tale, and consider yourself mas que advertido (strongly warned).

So one day, I was at a party at a friend-of-a-friend’s house. The host is a hilarious, hyperactive man with the most gigantic television I’ve ever seen, and he lives in an open-plan two-story loft apartment on Plaza Brazil. I didn’t know it at the time, but he likes board games.

Now this is something that I understand is normal in the United States. That people invite their friends over, eat, drink and are merry, all while playing a game. I like this idea, and it reminds me of Trivial Pursuit marathons in college, wherein I prayed that my Arts and Entertainment pie piece would be gained through the answer “Kermit the frog,” because that’s probably my best guess to most questions on that topic.

But I had played Cranium before, a board game which is part Pictionary, part claytionary (ok, I made that up, but you have to make things out of clay), part trivia game, and part charades. We were separated into teams, and a lucky group of three people I’d never met got me on their team. I could tell from the beginning that they were not amused by complete lack of cultural literacy in Spanish rhymes, canciones de cuna (lullabies), and the names of protagonists of television shows from Spain in the 80s. It was Arts and Entertainment again and again, and the answer was never “la rana René” (as Kermit is properly called in Spanish).

And then there was a vocabulary question, and my ears went up, ready to at least make eye contact with my teammates. The question concerned the word “nepotismo,” and I spoke up, saying, “it’s the one about family favoritism” and saw three people shrug at their previously unspeaking (and useless) teammate, as I shouted out the answer, and in a Quien quiere ser millonario (Who wants to be a millionaire) moment, the host asked “is that your final answer?” And it was, and we got the point, and they seemed to hate me just a little bit less.

Until.

The next round it was my turn to pick the card, and do the task. And my task was simple. I was to be blindfolded, and had to draw a picture of something in particular, to get my teammates to say the word/expression.

I saw my expression, felt confident, took the tiny golf pencil and the pad of paper in hand, closed my eyes and drew.

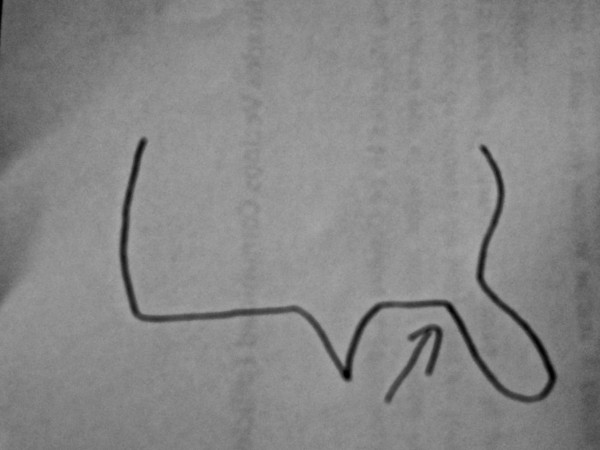

Imagine playing Pictionary with someone with a visual processing disorder such that they cannot understand visual representations. It was like that. Again and again, I drew the same thing, which looked approximately like this: (recreation, as I’m afraid to say the actual item was lost, but I also drew this with my eyes closed, and with a tiny golf pencil).

And then I drew an arrow, pointing to the thing that they should identify.

And I know that I am not a good artist, but I played “name the thing” (in Dutch) with a whole bunch of kids at a public school in rural Suriname, taking turns drawing figures in the dirt with a stick. I know I’m not that bad. I can at least draw coffee cups (tasse) and butterflies (vlinder) such that a group of six year olds can recognize them.

Nothing. Not even the typical “cat, bear, hat, teakettle, fireplace, oceanographer.” Nothing. Two minutes is a very long time to draw and listen for answers, when your drawing is essentially a simple line. I was blindfolded, so I couldn’t add any details.

“Qué es eso?” they finally asked, when the torturous two minutes were over. There may have been a xuxa in there, which is the hip way to spell chucha, which in this case means hell, as in “what the hell is that?. It goes between the qué and the es, in case you were wondering.

“El Golfo de México” I said, showing them the card. I had drawn the west coast lower border of the United States, complete with the ahem-shaped Florida peninsula, and cleverly drawn an arrow pointing to the area of the Atlantic ocean called “the Gulf of México.” I made my case.

“See? This is California, this is the border with Mexico, this funny looking thing is Texas, and then on the other side, you have Florida.”

“Oh. Why didn’t you draw a hat?

“Why would I have drawn a hat?” I said, thinking, sure, boat, maybe, oil refinery quizás, but a hat?

“sure, a Mexican hat. Or a margarita,” they said.

This is the point where I figured out that, as pleasant as a night of boardgames may be, if you are invited to play a culture-based game with a group of people whose culture you do not share, and who do not share yours, you should be prepared to be the weakest link, and shunned accordingly. Because these people are not your family.

Seeing that i would surely answer without hesitation “Florida!” cause the arrow points that way xD

yeah. Friends point out that the lack of Mexico makes it harder to know what I’m talking about. I should have put in strangled and drained mangrove swamps and oil refineries. Or you know, a hat.

Yep, I was thinking Florida too. I was just telling a friend in the US about times/places where differences in cultural references (like this) become very obvious–using the example of watching Forest Gump with a Chilean who did not catch any of the musical references in the film…

Anyway- now you know that to make it work here, you need to switch from la rana rené to a hat…

I once played a game where you draw a name out of a bag and have to get people to guess who the person is with my family in the UK. Some were current celebrities, others were book characters, historical figures, etc. It was interesting to see how even in English, with people who I’ve known my entire life, there were cultural differences that affected how well I did. For what it’s worth, I got Golfo de México from your drawing!

Emily for the win! I’m terrible at celebrity stuff though, and not a particularly good artist though, so I came to this game with several disadvantages!